Gen Z Years: Age Range, Birth Years & What We Know

The Labubu Effect: When Cute Dolls Signal Deeper Fault Lines

It’s easy to dismiss a plush toy as just that—a plush toy. But when a so-called "ugly-cute" doll from a Chinese toymaker starts generating billions in revenue, gets name-dropped by a stock exchange CEO, and causes celebrity frenzies, a data analyst like me takes notice. Bonnie Chan, the head honcho at Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing, wasn't just making small talk at the Fortune Global Forum in October. She was pointing to Labubu, Pop Mart's breakout star, as the prime example of "new consumption"—a phenomenon she described as emotionally driven purchases by China’s Gen Z. My analysis suggests she's right, but the story behind those surging sales isn't nearly as simple, or as cute, as the doll itself.

Pop Mart, a Beijing-headquartered retailer, pulled in a staggering 13 billion Chinese yuan ($1.9 billion) in revenue for the first half of 2025, a jump of over 200% year-over-year. Net income? Almost 400% up, hitting 4.5 billion yuan ($630 million). Labubu alone accounted for a third of that haul. Its shares on the Hang Seng Index soared over 125% before a recent 40% correction. Even after that significant dip, Pop Mart’s $37 billion market cap still eclipses industry giants like Hasbro, Mattel, and Sanrio combined. That’s not just a toy company; it’s a cultural juggernaut, built on the back of blind boxes and collectible IP. Wang Ning, Pop Mart’s founder, is now sitting on an $18 billion fortune, according to Bloomberg. Pretty good for selling mystery figurines.

But here’s where my skepticism kicks in: The hype, as CEO Wang Ning himself admits, is hard to forecast. And sure enough, Labubu mania has already started to cool. Declining secondary market prices and a leaked conversation from a Pop Mart salesperson suggesting boxes are overpriced sent the company’s market value plunging by almost $2.2 billion in a single day in early November. This isn't just a blip; it's a data point. While HSBC analysts are quick to dismiss comparisons to the Beanie Baby bubble of the 90s, I’ve looked at hundreds of these market surges, and the pattern of rapid ascent followed by sharp corrections when cracks appear is disturbingly familiar. The question isn't if the Labubu craze will fade, but what it reveals about the underlying currents that propelled it in the first place. It's like watching a pressure cooker hiss; the steam might be cute, but the pressure building underneath is the real story.

Decoding the Generational Equation: More Than Just 'Emotional' Spending

What really drives this "new consumption" among Gen Z, both in China and increasingly globally? The narrative spun by consultants like ChoZan’s Ashley Dudarenok—that Pop Mart acts more like "cultural anthropologists than toymakers"—is compelling, but it glosses over the fundamental economic realities shaping this generation. Analysts tied the Labubu craze to young urban shoppers, frustrated by limited career options and social mobility, spending on hobbies and small pleasures rather than big-ticket items like a home. This isn't just "emotional"; it's a pragmatic pivot in the face of systemic constraints. If you can’t afford the down payment on a house, a $15 blind box offering a moment of dopamine and a tiny piece of collectible art starts to look pretty appealing. It’s a micro-investment in personal identity when macro-investments feel out of reach. Labubus revealed the 'new consumption' trend among China's Gen Z that's now spreading overseas

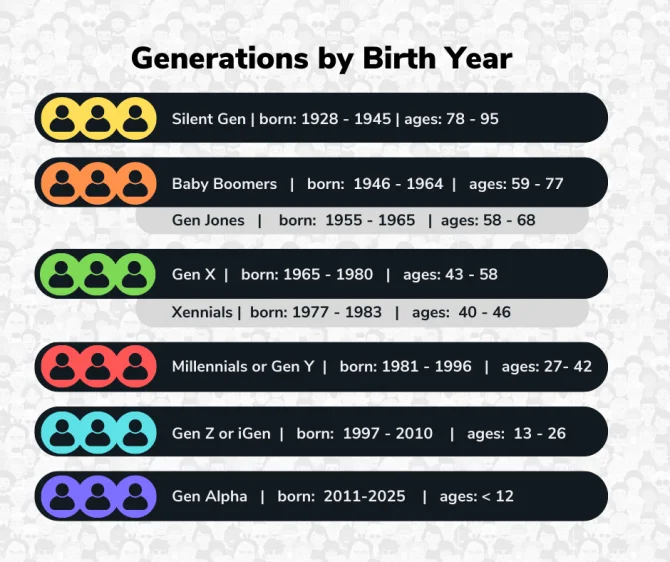

This phenomenon isn’t isolated to China. Globally, Gen Z (roughly those born between the mid-90s and early 2010s) has grown up in a turbulent era: economic crises, political polarization, a pandemic, and an increasingly precarious future. They're often burdened with student debt, facing stagnant wages, and inheriting a planet on fire. My own analysis of generational sentiment (treating online discussions, memes, and surveys as a qualitative, anecdotal data set) shows a distinct pattern: a dark humor about death, a pervasive sense of economic anxiety, and a deep-seated frustration with existing power structures.

Consider the data from a recent survey on fears about dying: Boomers dread "decline," Gen X panics about "logistics," Millennials fear "unlived potential," but Gen Z? They're scared of how they'll die, often citing school shootings, climate catastrophes, or police violence. A 20-year-old student put it bluntly: "Rich people get to die peacefully in their beds. The rest of us get to die in debt or in some mass casualty event." This isn't just morbid; it’s a reflection of a generation that has grown up watching death stream live, surrounded by inequality.

This economic and existential angst isn’t just fueling "new consumption"; it's also fueling political instability. Youthful protestors have already toppled governments in Madagascar and Nepal in 2025, and forced concessions elsewhere, like in Bulgaria just weeks before its euro zone entry. The median age in Cameroon, for instance, was 19 in 2024, yet it's led by a 92-year-old president. This demographic mismatch is a ticking time bomb. What makes these Gen Z-led movements particularly potent and unpredictable is their genesis on social media, often lacking a central figurehead. They erupt spontaneously, a direct consequence of a generation that feels unheard, overlooked, and economically squeezed.

The Unseen Hand of Frustration

The Labubu craze, then, isn't just a fleeting trend in collectible toys; it's a quantifiable symptom of a generation navigating profound economic and existential uncertainty. The immediate gratification, the sense of community around collecting, the expression of personality through affordable items—these are all coping mechanisms for a generation that feels a distinct lack of control over their broader circumstances. When you can't control the macro, you obsess over the micro. Pop Mart's success, and its subsequent market volatility, is a stark reminder that what appears on the surface as whimsical consumerism often has deeper, more volatile roots. Investors betting on "new consumption" need to understand that this isn’t just about shifting tastes; it’s about a generational shift in worldview, one that carries significant, often unpredictable, economic and political risks.